When a patient picks up a generic pill, they don’t just see a cheaper version of their brand-name drug. They see a color, a shape, a size - and sometimes, they see something that doesn’t match their beliefs. For many people around the world, the way a medicine looks, what it’s made of, and even how it’s explained can make the difference between taking it - or refusing it altogether.

Why a Generic Pill Might Not Be Accepted

In the U.S., 70% of all prescriptions filled are for generic drugs. In Europe, it’s the same. But that number doesn’t tell the whole story. Behind those stats are patients who won’t take their medication because it contains gelatin made from pork, because it’s the wrong color, or because they’ve been told - by family, community, or past experience - that generics are weaker. Take a Muslim patient prescribed a generic blood pressure pill. The branded version came in a vegetarian capsule. The generic? Gelatin. Not just any gelatin - pork-based. Even though the active ingredient is identical, the patient refuses it. Not out of ignorance. Out of faith. A 2023 study found that 63% of pharmacists in urban U.S. clinics get at least one question a week about whether a medication contains animal products, alcohol, or other substances forbidden by religious law. It’s not just religion. In some African and Caribbean communities, white pills are associated with poison or weakness. Brightly colored pills - red, yellow, green - are trusted more. A patient might refuse a white generic tablet, even if it’s exactly what their doctor ordered, because they believe only the colorful branded version “works.”The Hidden Ingredients That Matter More Than You Think

Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient as the brand-name version. That’s the law. But the rest? The fillers, the dyes, the coatings, the capsules - those are called excipients. And they’re not regulated the same way across countries. In the U.S., only 37% of generic drug labels list all excipients in detail. In the EU, it’s 68%. That means a patient in London might know their generic metformin is free of pork gelatin. A patient in Chicago might not. And if they’re from a Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, or vegan background, that difference matters. One pharmacist in Detroit told a researcher she spent two hours calling manufacturers just to find a liquid form of a diabetes medication without alcohol. The patient, a Muslim woman, had refused the pill because she thought the alcohol content was haram. She wasn’t wrong to worry - some liquid generics do contain ethanol as a stabilizer. But without clear labeling, how was she supposed to know?Color, Shape, and the Myth of “Stronger” Medicine

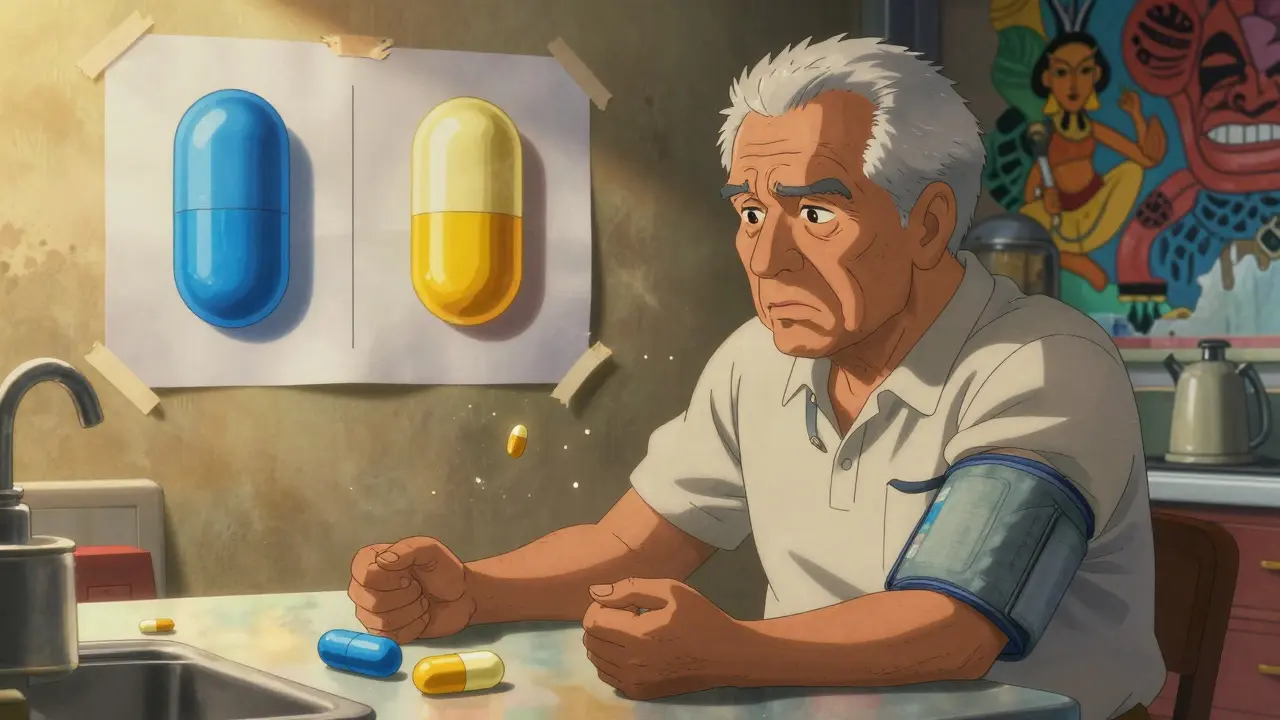

In many cultures, the appearance of medicine is tied to its perceived strength. A large, branded pill with a logo feels powerful. A small, plain generic tablet? It looks like a sugar pill. A 2022 FDA survey found that 28% of African American patients believed generic drugs were less effective than brand-name ones. Only 15% of non-Hispanic White patients felt the same. Why the gap? Historical mistrust. Medical discrimination. Stories passed down through families: “They gave us the cheap stuff back then.” One elderly Hispanic man in Miami stopped taking his generic cholesterol pill because it changed from blue to yellow. His daughter had to call the pharmacy to confirm it was the same drug. The pharmacist had to print out a side-by-side image of both versions - branded and generic - to show him they contained the same medicine. He still didn’t trust it. “The color changed,” he said. “That means it’s not the same.”Language Isn’t Just About Words - It’s About Trust

If a patient can’t read the instructions, they won’t take the medicine correctly. But even if they can read it, the way the information is presented matters. A Spanish-speaking patient in Texas was told by her doctor to take her generic antidepressant “once daily.” She took it three times a day because the word “daily” was translated as “cada día,” which she interpreted as “every day, but maybe more if needed.” The pharmacist didn’t catch it because the label was in English only. Good patient education isn’t just about translating text. It’s about understanding cultural context. In some Asian cultures, directly saying “this medicine might not work” is considered rude. So a patient might nod along, then quietly stop taking the drug because they don’t believe in it. In other cultures, asking too many questions is seen as disrespectful to the doctor - so patients stay silent even when confused.

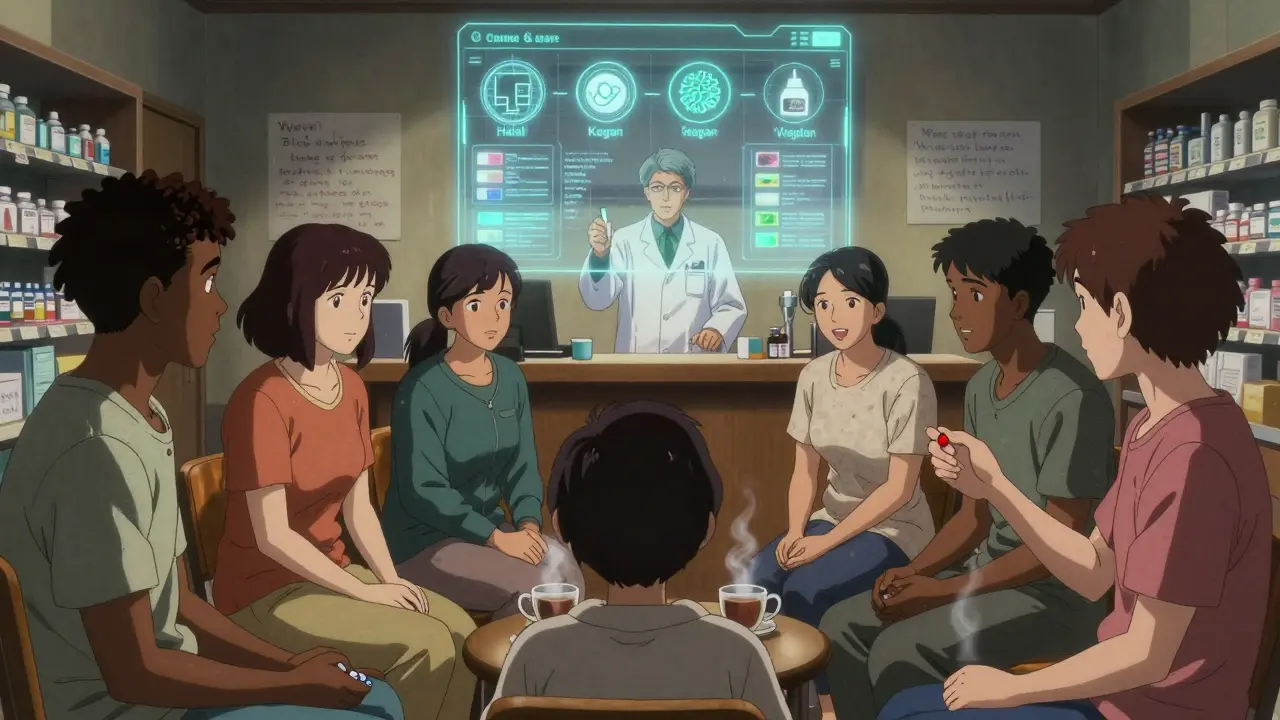

What Works: Real Solutions from the Field

Some pharmacies are starting to fix this. In Philadelphia, a chain launched a “Cultural Formulary” - a digital database that lets pharmacists instantly check if a generic medication contains pork gelatin, alcohol, or shellfish-derived ingredients. They’ve mapped over 200 common generics. It used to take hours. Now it takes seconds. In Toronto, pharmacists now offer visual aids - color-coded charts showing which pills are safe for which dietary or religious needs. They don’t just hand out a leaflet. They sit down. They ask: “Is there anything in your medicine that would go against your beliefs?” Teva Pharmaceutical started a program in 2023 to label all generics with clear excipient details - halal, kosher, vegan - by the end of 2024. Sandoz is doing the same. These aren’t charity projects. They’re business moves. The U.S. market alone has $12.4 billion in unmet need among minority populations for hypertension and diabetes meds. People will pay for trust.Training Isn’t Optional - It’s Essential

Only 22% of U.S. community pharmacies have formal training on cultural considerations for generics. That’s not enough. Pharmacists need to know:- Which excipients are forbidden in Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and vegan lifestyles

- How color and shape influence patient perception

- How to ask open-ended questions without sounding invasive

- Where to find reliable, up-to-date formulation data

The Bigger Picture: Why This Isn’t Just About Pills

This isn’t just about making sure someone takes their blood pressure medicine. It’s about dignity. It’s about equity. It’s about recognizing that health care isn’t one-size-fits-all - even when the pill looks the same. The Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act (FDORA) of 2022 pushed for better inclusion of diverse populations in clinical trials. That’s important. But if the medicine you’re prescribed doesn’t match your values, even the best science won’t help. Generic drugs are supposed to make care more accessible. But if cultural barriers stop people from taking them, then they’re not accessible at all. The solution isn’t more money. It’s more awareness. More training. More transparency. And most of all - more respect for the fact that culture shapes how we see health, sickness, and healing.

What Patients Can Do

If you’re prescribed a generic:- Ask: “Does this contain gelatin, alcohol, or animal products?”

- Ask: “Why does it look different from my old pill?”

- Ask: “Can you show me the ingredients?”

- Bring a family member or interpreter if you’re not confident in the language

- Don’t be afraid to say: “I don’t feel comfortable taking this.”

What Pharmacies and Providers Can Do

- Build a cultural excipient database for your pharmacy - Train staff on religious and cultural medication needs - Use visual aids, not just text, for instructions - Partner with community leaders to co-create educational materials - Advocate for better labeling from manufacturersWhat’s Next?

By 2027, 65% of top generic manufacturers say they’ll include cultural considerations in product design. That’s progress. But it’s not fast enough. The truth is, we’ve known for years that culture affects health outcomes. Now, we’re finally starting to see it affect how medicine is made - and who gets to take it. The future of generics isn’t just cheaper pills. It’s smarter, kinder, more respectful care. And that’s something every patient - no matter their background - deserves.Why do some people refuse generic medications even when they’re cheaper?

Many people refuse generics because of cultural, religious, or personal beliefs tied to the pill’s appearance, color, or ingredients. For example, some Muslim and Jewish patients avoid medications with pork gelatin or alcohol. Others believe that different shapes or colors mean the medicine is weaker, especially if they’ve had negative experiences with the healthcare system in the past. These aren’t irrational fears - they’re rooted in real cultural values and historical mistrust.

Are generic drugs really the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes, by law, generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient, dosage, and effectiveness as the brand-name version. But they can differ in color, shape, size, and inactive ingredients - called excipients. These differences don’t affect how the drug works, but they can affect whether a patient will take it. For example, a generic might use gelatin from pork, while the brand version uses plant-based capsules. That’s not a difference in strength - it’s a difference in culture.

How can I find out what’s in my generic medication?

Ask your pharmacist. They can look up the full list of excipients - ingredients like dyes, fillers, and coatings - that aren’t always listed clearly on the label. In the U.S., only 37% of generic labels include full ingredient details. In the EU, it’s 68%. If you’re concerned about pork, alcohol, or allergens, don’t assume. Always ask. Some pharmacies now have digital tools that instantly show you which generics are halal, kosher, or vegan.

Why do some cultures prefer certain pill colors?

Color carries meaning. In some African and Caribbean communities, white pills are associated with weakness or poison, while red or yellow pills are seen as powerful and healing. In parts of Asia, green means balance and health. In Western cultures, blue is often calming. If a generic changes color from what a patient is used to, they may think it’s a different drug - even if it’s chemically identical. Pharmacists are learning to use color charts to help patients understand that appearance doesn’t equal effectiveness.

What’s being done to improve culturally competent generic medication use?

Major companies like Teva and Sandoz are now labeling generics with halal, kosher, and vegan certifications. Some pharmacies have created digital databases to quickly find alternatives that match cultural needs. Training programs for pharmacists are growing, though still rare. The FDA and EU regulators are pushing for better labeling. But the biggest change is cultural: healthcare providers are finally listening to patients - not just prescribing to them.

Siobhan K.

December 21, 2025 AT 22:30At this point, we’re treating medication like a fashion statement. Next thing you know, people will refuse insulin because it’s not "artisanal" enough.

Brian Furnell

December 22, 2025 AT 13:25Jason Silva

December 24, 2025 AT 01:00mukesh matav

December 25, 2025 AT 05:51Peggy Adams

December 26, 2025 AT 06:57Sarah Williams

December 27, 2025 AT 08:26Theo Newbold

December 28, 2025 AT 22:45Jackie Be

December 30, 2025 AT 12:47John Hay

December 31, 2025 AT 06:51Jon Paramore

January 2, 2026 AT 04:31Swapneel Mehta

January 2, 2026 AT 10:18Stacey Smith

January 4, 2026 AT 02:31Ben Warren

January 5, 2026 AT 11:20