Every year, thousands of patients in hospitals and clinics across the U.S. and U.K. are harmed not because of a wrong diagnosis, but because someone misheard a medication order. A nurse hears "Hydralazine" but the doctor said "Hydroxyzine". A resident says "fifteen milligrams" but the pharmacist hears "five hundred". These aren’t rare mistakes-they’re predictable ones. And they happen because verbal prescriptions, while necessary, are dangerously easy to mess up.

Why Verbal Prescriptions Still Exist

You might think we’d have eliminated verbal prescriptions by now. After all, electronic systems are everywhere. But in real-world medicine, things don’t always go as planned. Surgeons in the operating room can’t stop to type orders. Emergency room staff need to act in seconds. A patient’s blood pressure is crashing, and the only way to get the right drug to them fast is to say it out loud. That’s why verbal orders still make up about 10-15% of all medication orders in hospitals, and even higher-20-25%-in outpatient clinics. They’re not going away. The question isn’t whether to use them, but how to use them safely.The Hidden Danger: Sound-Alike Drug Names

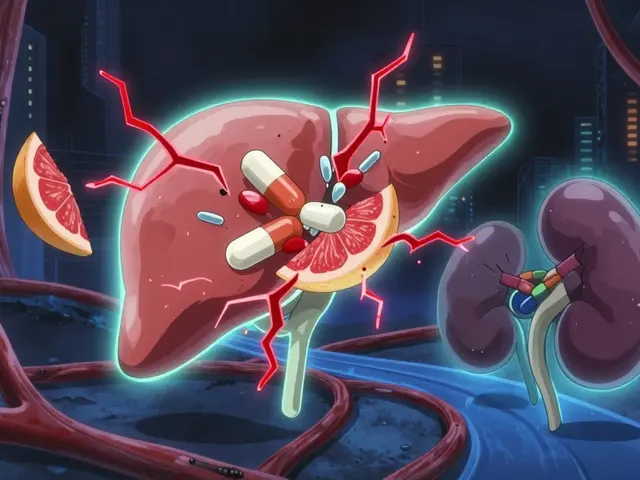

One of the biggest killers in verbal prescriptions isn’t bad handwriting-it’s bad hearing. Drugs with similar names are the silent enemy. Celebrex and Celexa. Zyprexa and Zyrtec. Hydralazine and Hydroxyzine. These aren’t just confusing-they’re deadly. According to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, 34% of all verbal order errors involve sound-alike drug names. In one documented case, a premature infant received the wrong antibiotic because the nurse heard "ampicillin" as "gentamicin" during a chaotic transfer. The child nearly died. In another, a patient was given a 10-fold overdose of hydralazine because the prescriber didn’t spell it out. The fix? Spell every drug name aloud-letter by letter. Don’t say "Ampicillin". Say "A-M-P-I-C-I-L-L-I-N". It takes five extra seconds. But those seconds save lives.The Read-Back Rule: Your Lifeline

The single most effective safety tool in verbal prescribing isn’t new software or a fancy app. It’s a simple habit: read-back verification. Here’s how it works:- The prescriber says the full order: medication, dose, route, frequency, and reason.

- The receiver repeats it back word-for-word.

- The prescriber confirms: "Yes, that’s correct."

Numbers That Can Kill

It’s not just drug names. Numbers are just as dangerous. Saying "15 milligrams" can be misheard as "50 milligrams" or even "150". The fix? Say numbers two ways. Say "fifteen milligrams, that’s one-five milligrams". This forces the listener to process the information twice. It’s a tiny change that cuts confusion dramatically. Same goes for decimals. Never say ".5 mg". Say "zero point five milligrams". A missing zero can turn a safe dose into a lethal one.

High-Alert Medications: When Verbal Orders Are Forbidden

Some drugs are too risky to order verbally-unless it’s a true emergency. These include:- Insulin

- Heparin

- Chemotherapy agents

- Opioids like morphine or fentanyl

What Must Be Documented-And When

A verbal order isn’t real until it’s written down. And not just scribbled on a sticky note. It must be entered into the electronic health record (EHR) immediately by the receiver or a designated assistant. The record must include:- Patient’s full name and date of birth

- Medication name (spelled out)

- Dose with units (e.g., "500 milligrams", not "500 mg")

- Route (e.g., "by mouth", not "PO")

- Frequency (e.g., "twice daily", not "BID")

- Reason or indication (e.g., "for fever above 101°F")

- Name and title of the prescriber

- Time and date the order was given

- Time and date the order was authenticated

What to Avoid Like the Plague

There are words and abbreviations that have no place in verbal orders. Ever.- Don’t use BID, TID, QHS, or QD. Say "twice daily," "three times daily," "at bedtime," "once daily."

- Don’t say "PO". Say "by mouth."

- Don’t say "SC" or "IM". Say "under the skin" or "into the muscle."

- Never say "U" for units. Say "units." A handwritten "U" looks like a "4"-and that’s how people get overdosed.

Real Stories, Real Consequences

In 2006, a NICU nurse received a verbal order for two antibiotics: ampicillin 200 mg and gentamicin 5 mg IV. The prescriber said them fast, one after the other. The nurse wrote down "ampicillin 200 mg and gentamicin 50 mg IV." The infant was given 10 times the intended dose of gentamicin. The child suffered permanent kidney damage. Another case: a diabetic patient was given insulin via verbal order. The prescriber said "10 units". The nurse heard "100 units". The patient went into a coma. Neither used read-back. Neither spelled out the number. These aren’t outliers. They’re textbook failures.What Works: The Best Practices That Save Lives

Here’s what high-performing teams do differently:- Use standardized scripts: "I’m calling in a verbal order for [medication], [dose], [route], [frequency], for [indication]."

- Pause after each part: Don’t rush. Let the receiver absorb each piece.

- Use phonetic spelling: A-M-P-I-C-I-L-L-I-N. H-Y-D-R-A-L-A-Z-I-N-E.

- Double the numbers: "Fifteen milligrams, that’s one-five milligrams."

- Always read back: Even if the prescriber is your best friend. Even if you’ve worked together for 10 years.

- Document immediately: Don’t wait. Don’t rely on memory.

- Speak slowly, clearly, and in a quiet space: No background noise. No yelling. No distractions.

What’s Changing? The Future of Verbal Prescriptions

Technology is slowly reducing the need for verbal orders. Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) systems cut verbal order rates from 22% to 10% in hospitals between 2006 and 2019. By 2025, KLAS Research predicts that number will drop to 5-8%. But here’s the truth: even with perfect tech, some situations will always need a voice. Emergencies. Sterile fields. Power outages. System crashes. That’s why experts like Dr. Robert Wachter say: "Verbal orders aren’t going away. But the way we handle them must evolve." The FDA is now working on standardizing how high-risk drug names are pronounced. States are making read-back mandatory in licensure rules. Hospitals are training staff like pilots-using checklists, simulations, and peer feedback.Final Thought: It’s Not About Trust. It’s About Process.

You might think, "My doctor knows what they’re doing. I trust them." But safety isn’t about trust. It’s about systems. One nurse on AllNurses.com wrote: "I once asked a doctor to spell hydralazine. He rolled his eyes. I still did it. Later, I found out he’d meant hydroxyzine. I caught it because I asked. That’s why I always ask." You don’t need to be the hero. You just need to be the one who follows the rules-even when it’s inconvenient. Because in healthcare, the most dangerous word isn’t "error." It’s "I thought."Are verbal prescriptions still allowed in hospitals?

Yes, verbal prescriptions are still allowed under CMS and The Joint Commission regulations. They’re permitted in emergencies, during surgeries, or when electronic systems aren’t available. But they must follow strict safety rules, including read-back verification and immediate documentation. Many hospitals now limit them to only the most urgent cases.

Why is read-back so important for verbal prescriptions?

Read-back forces the receiver to repeat the order exactly as given, giving the prescriber a chance to catch mistakes before they reach the patient. Studies show this single step reduces medication errors by up to 50%. It’s not about doubting the provider-it’s about catching human errors like mishearing, distraction, or fatigue.

What drugs should never be ordered verbally?

High-alert medications like insulin, heparin, chemotherapy agents, and opioids should only be ordered verbally in true emergencies. Many hospitals and state health departments prohibit verbal orders for these drugs under normal conditions because even small mistakes can be fatal. Always check your facility’s policy.

How do I avoid confusion with drug names that sound alike?

Always spell out the full drug name letter by letter. Don’t say "Celexa"-say "C-E-L-E-X-A." Use the ISMP’s list of dangerous sound-alike pairs as a reference. If you’re unsure, ask: "Can you spell that?" or "Is that hydralazine or hydroxyzine?" It’s better to sound cautious than to be wrong.

Can assistants enter verbal orders into the EHR?

Yes, since 2022, CMS allows authorized documentation assistants to enter verbal orders into the electronic health record under direct supervision of the prescriber. But the prescriber must still verify the order and authenticate it within 48 hours. The assistant doesn’t replace accountability-they just help with documentation.

What’s the biggest mistake people make with verbal prescriptions?

The biggest mistake is skipping the read-back or assuming the other person heard correctly. People think, "I’ve worked with this doctor for years, I know what they mean." But errors happen because of fatigue, noise, distractions, or language barriers-not lack of skill. The safest approach is always to verify, spell, and document-even when it feels awkward.

Mindee Coulter

January 27, 2026 AT 22:16Just read this on my break and holy hell this is the most important thing I've seen all week. Spell out the damn drug names. Always.

matthew martin

January 29, 2026 AT 02:13I've been in the ER for 12 years. The one time I didn't read back? We gave a kid 10x the insulin dose. He's fine now, but I still wake up sweating. Never skip the read-back. Ever. Even if the doc is your buddy. Even if you're tired. Even if the unit's a zoo.

It's not about trust. It's about being human.

Chris Urdilas

January 29, 2026 AT 16:20So let me get this straight - we’re still using voice commands in a hospital like it’s 1998? And the solution is to say 'one-five milligrams' instead of '15'? I love how we solve tech problems with more talking.

Meanwhile, my phone autocorrects 'Hydralazine' to 'Hydroxyzine' and I'm not even a doctor.

Rose Palmer

January 31, 2026 AT 00:57Thank you for outlining these protocols with such clarity. As a clinical educator, I’ve trained dozens of new nurses on verbal order safety, and the read-back protocol remains the single most effective intervention we have. It’s not about suspicion - it’s about standardization. When we normalize asking for clarification, we reduce stigma and increase safety. I encourage every facility to role-play these scenarios monthly. It’s not extra work - it’s risk mitigation.

Also, please note: the use of 'U' for units is still a leading cause of preventable harm. Always say 'units.' Every time. No exceptions.

Irebami Soyinka

February 1, 2026 AT 20:52Y'all in the US still think this is a new problem? In Nigeria, we’ve been shouting drug names since the 80s - no EHR, no power, just a nurse yelling 'A-M-P-I-C-I-L-L-I-N!' across the ward while goats walk through. You think this is hard? Try doing it during a blackout with a generator sputtering and 12 crying babies in the room. We don’t have 'read-back culture' - we have 'survival culture.' And we don’t make mistakes. We just don’t survive if we do.

Stop acting like this is some fancy American innovation. We’ve been doing this right when your hospitals were still using pen and paper.

Brittany Fiddes

February 3, 2026 AT 18:17Oh, so now we’re blaming the nurses for not reading back? How quaint. In Britain, we don’t have this problem because we have a proper healthcare system. In your chaotic, profit-driven mess, you let interns bark orders like they’re in a warzone. We don’t need 'phonetic spelling' - we need universal healthcare. And while we're at it, maybe stop letting Americans think they invented safety protocols.

Also, 'C-E-L-E-X-A'? Please. We say 'C-E-L-E-X-A' like we say 'pneumonia.' With dignity. You lot just scream everything like you're at a football match.