When a brand-name drug hits the market, its patent gives the maker exclusive rights to sell it-often for 20 years. But that clock doesn’t run the whole time. The FDA grants up to five extra years of exclusivity for clinical trials, and drugmakers pile on additional patents for minor changes: a new pill shape, a different coating, a slightly altered dosage. By 2024, the average drug had 17.3 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. That’s not innovation-it’s a legal wall to keep generics out.

How generics break through the patent wall

Enter Paragraph IV certification. It’s not a loophole. It’s a legal tool built into the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 to balance innovation with access. When a generic company wants to sell a cheaper version of a branded drug, they file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). But if the drug still has active patents, they can’t just copy it. Instead, they must file a Paragraph IV certification: a formal, legally binding statement that says one or more of those patents are invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed by their product.This isn’t a bluff. It’s a trigger. Under 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2), submitting an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is treated as an “artificial act of infringement.” That means the brand company can sue before the generic drug is even made. It sounds backwards-why sue before anything’s sold?-but it’s the only way the system works. Without this rule, generics would have to wait until they launched, risk massive damages if they lost, and brands would have no way to stop them early. The law created a controlled battlefield.

The 20-day notice and the 45-day clock

Once the FDA accepts the ANDA, the generic company has exactly 20 days to send a detailed notice to the brand-name manufacturer and the patent holder. This isn’t a form letter. It has to lay out the legal and scientific reasons why their drug won’t infringe-or why the patent is flawed. Maybe their manufacturing process is different. Maybe the patent only covers a use the generic won’t market. Maybe the patent was obvious and shouldn’t have been granted in the first place.Then the clock starts ticking for the brand. They have 45 days to file a patent infringement lawsuit. If they do, the FDA puts a 30-month hold on approving the generic. That’s not a guarantee of delay-it’s a pause button. The court can end it sooner if they rule in favor of the generic. Or the case can drag on, pushing the stay past 30 months. In 2023, the average stay lasted 36.2 months because of procedural delays.

The $500 million prize: 180 days of exclusivity

The real incentive for generics isn’t just to save patients money-it’s to make billions. The first company to file a successful Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of market exclusivity. No other generic can enter during that time. For a blockbuster drug like Humira, which brought in over $20 billion a year, that 180-day window can mean $500 million in pure profit.That’s why companies like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz spend millions on legal teams just to be first. In 2024, Teva filed 147 Paragraph IV certifications. That’s not luck. It’s strategy. They study patent lists, analyze litigation trends, and time their filings to beat competitors. But being first doesn’t always mean winning. Many generics end up settling with the brand. In 2024, 78% of Paragraph IV cases ended in settlement-and 68% of those included “pay-for-delay” deals, where the brand pays the generic to hold off on launching. The FTC sued 17 of these deals in 2023-2024, calling them anti-competitive.

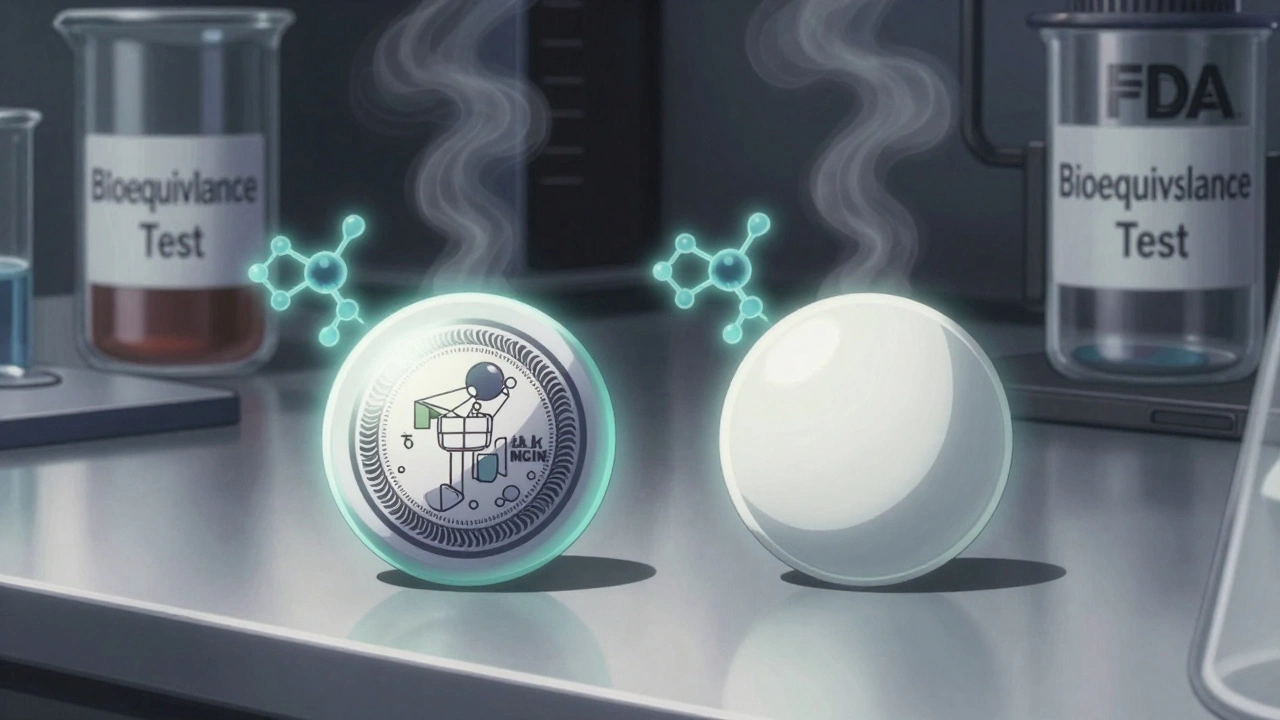

Carve-outs and skinny labels: Winning without fighting

Sometimes, generics don’t need to challenge every patent. They use something called a Section viii carve-out. If a drug is approved for three conditions-say, Type 2 diabetes, heart failure, and weight loss-but only the patent covers weight loss, the generic can ask the FDA to approve it only for the other two uses. They remove the patented indication from their label. That’s called a “skinny label.”It’s legal. It’s smart. And it’s used in about 37% of Paragraph IV filings. A generic can launch months earlier than if they tried to fight the patent head-on. No lawsuit. No 30-month stay. Just a cleaner label and a faster path to market. This tactic is especially common for drugs with multiple approved uses, like antidepressants or diabetes medications.

Why this system is both brilliant and broken

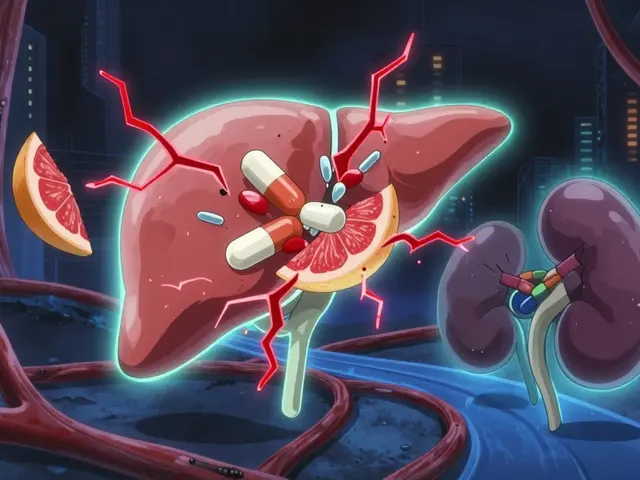

The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to get generics to market faster without crushing innovation. And it worked. Since 1984, generics have saved U.S. consumers $2.2 trillion. In 2024 alone, they saved $192 billion. Ninety percent of brand-name drugs now have generic versions.But the system is under strain. Brand companies now list an average of 17 patents per drug-up from 7 in 2005. That’s called “patent thicketing.” They don’t need all of them to be strong. They just need enough to make litigation expensive and slow. Generic companies spend an average of $12.3 million per Paragraph IV challenge, and cases take nearly 29 months to resolve. That’s why many smaller generics can’t compete. Only the big players have the resources to fight.

And then there’s “product hopping.” When a patent is about to expire, some brands release a slightly modified version of the drug-say, a pill that dissolves in the mouth instead of being swallowed-and get a new patent. The generic company has to start over. In 2024, 31% of Paragraph IV challenges targeted drugs that had been reformulated just before generic entry.

What’s changing in 2025 and beyond

The FDA’s 2022 rules tried to close loopholes. Now, if a court rules a patent is infringed, the generic can’t just tweak their application and try again. They have to file a new certification that matches the court’s decision. That stops “litigation shopping”-where companies keep filing until they find a judge who rules their way.In June 2025, new data showed generic success rates in court jumped from 41% (2003-2019) to 58% (2020-2025). Why? Supreme Court rulings made it harder to patent obvious or vague claims. Patents on things like “a tablet containing the drug” without a novel delivery method are now more likely to be thrown out.

And the FDA is proposing new rules for 2026: brand companies will have to justify every patent they list in the Orange Book. If they can’t prove it’s truly related to the drug’s use, it gets removed. Analysts predict this could cut patent thickets by 30-40%.

The FTC is also stepping up. Their 2025 plan targets pay-for-delay deals with more lawsuits. If they succeed, generics could enter the market 4-6 months earlier on average.

Who wins when Paragraph IV works?

Patients win. Lower prices. Faster access. A pill that costs $5 instead of $500.Generic manufacturers win too-when they get the 180-day exclusivity and avoid settlements. Teva made $1.2 billion in 2023 from Paragraph IV exclusivity alone.

But the system still favors the deep pockets. Smaller companies struggle. The legal costs are too high. The delays are too long. And the brand companies still have tools to push back-patent thickets, product hopping, pay-for-delay deals.

Paragraph IV certification isn’t perfect. But it’s the most powerful tool we have to break monopolies on life-saving drugs. Without it, generics wouldn’t be able to challenge patents before launch. And without that, most brand-name drugs would stay expensive for years longer than they should.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement made by a generic drug company when filing an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). It asserts that one or more patents listed for the brand-name drug in the FDA’s Orange Book are invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product. This triggers a patent lawsuit from the brand company, starting a legal process that can lead to early generic market entry.

Why is Paragraph IV called an “artificial act of infringement”?

Under U.S. patent law (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2)), submitting an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is legally treated as an act of patent infringement-even though no drug has been sold yet. This allows brand companies to sue before the generic enters the market, preventing them from waiting until real harm occurs. It’s a legal fiction designed to resolve patent disputes early.

What happens after a Paragraph IV certification is filed?

The generic company must notify the brand and patent holders within 20 days. The brand has 45 days to file a lawsuit. If they do, the FDA automatically delays approval of the generic for 30 months-unless the court rules earlier. The first generic to file gets 180 days of market exclusivity if they win.

What is a “skinny label” and how does it help generics?

A “skinny label” is when a generic drug omits a patented use from its FDA-approved labeling. For example, if a drug treats both diabetes and obesity, but only the obesity use is patented, the generic can seek approval only for diabetes. This lets them launch without challenging the patent at all, avoiding litigation and delays.

Why do some generic companies settle with brand manufacturers?

Settlements often involve “pay-for-delay” agreements, where the brand pays the generic to delay launch. This avoids the cost and risk of a trial. But it also keeps prices high. The FTC considers these deals anti-competitive and has sued 17 such agreements since 2023.

How much does a Paragraph IV challenge cost?

The average legal cost is $12.3 million per case, with trials lasting about 29 months. Companies also face holding costs if the 30-month stay is extended-adding $8.7 million or more in lost revenue per delayed product. Only large generic manufacturers can typically afford these costs.

What’s the impact of Paragraph IV on drug prices?

Since 1984, Paragraph IV challenges have saved U.S. consumers $2.2 trillion. In 2024, they saved $192 billion in a single year. Generic drugs now make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S., largely because of this system.

Which companies file the most Paragraph IV certifications?

In 2024, Teva led with 147 filings, followed by Mylan (112), Sandoz (98), and Hikma (87). These companies have dedicated legal and regulatory teams focused on patent challenges. Brand drugs like Humira, Trulicity, and Eliquis face the most challenges-often from multiple generics at once.

What’s next for generic drug competition?

The future of Paragraph IV isn’t just about more lawsuits. It’s about smarter rules. The proposed 2026 FDA rule requiring brand companies to justify every patent listed could reduce patent thickets by up to 40%. That means fewer fake patents, fewer delays, and faster generic entry.Meanwhile, biosimilars-generic versions of biologic drugs-don’t have a Paragraph IV equivalent. That’s a growing problem. Biologics are now the most expensive drugs on the market, and their patents are harder to challenge. Without a similar system, patients will keep paying premium prices for years.

For now, Paragraph IV remains the most effective tool we have to bring down drug prices. It’s not perfect. But without it, the system would be broken. And patients would pay more-for longer.

Jeffrey Hu

January 8, 2026 AT 19:15Bro, the whole Paragraph IV system is just a legal circus. Brands file 17 patents on the same pill because they can. Generics spend millions just to get to the starting line. And the FDA? They’re just watching like it’s a reality show. This isn’t innovation-it’s rent-seeking with a law degree.

Micheal Murdoch

January 10, 2026 AT 09:35It’s funny how we celebrate innovation but punish competition. The real miracle isn’t the drug-it’s that a generic company can survive the legal gauntlet and still sell a pill for $5 instead of $500. We talk about access like it’s a privilege, but it’s a right. The system’s broken, but it’s still the only thing keeping Big Pharma from pricing medicine out of existence.

I’ve seen people choose between insulin and rent. That’s not a market failure-that’s a moral one. Paragraph IV isn’t perfect, but without it, we’d be back to the 90s, where a single pill could cost a year’s salary.

It’s not about who wins the lawsuit. It’s about who wins the right to live.

Jenci Spradlin

January 10, 2026 AT 10:51lemme tell u somethin… the 180 day exclusivity is the real MVP. Teva’s not some saint-they’re just the first to jump in the ring and not get knocked out. I read somewhere that 78% of these cases end in a pay-for-delay deal. That’s just bribery with a law firm on speed dial.

And don’t get me started on product hopping. They change the damn coating and call it a new drug. My grandma’s pill dissolves in her mouth now? Cool. But it’s the same damn chemical. Why am I paying $400 for that?

Lindsey Wellmann

January 10, 2026 AT 21:32THEY PAID GENERICS TO NOT SELL DRUGS??? 😱💸

THIS ISN’T CAPITALISM. THIS IS A SCAM. 🤬

FTC, DO YOUR JOB. 🙏

Aron Veldhuizen

January 12, 2026 AT 00:40You’re all missing the philosophical core here. The patent system was never meant to be a weapon-it was meant to incentivize creation. But now, creation is a sideshow. The real product is litigation. The real innovation is legal obfuscation. We’ve turned medicine into a contract law exercise. What does that say about our values? Are we a society that values health-or litigation outcomes?

And let’s not pretend ‘skinny labels’ are ethical. They’re legal loopholes dressed as solutions. If a drug treats three conditions, why should one patient be denied access to the full benefit because of a corporate chess game?

Perhaps the real question isn’t how to fix Paragraph IV-but whether we should abolish patents on life-saving drugs entirely.

Ian Long

January 13, 2026 AT 17:19Look, I get why the big generics win. They’ve got lawyers on retainer and spreadsheets thicker than my college textbooks. But what about the little guys? The ones who can’t afford a $12 million legal bill? They get pushed out. And then we wonder why drug prices stay high.

The FDA’s new rules might help-but only if they actually enforce them. Last time they promised to clean up the Orange Book, we got a pamphlet and a pat on the back.

We need to stop treating this like a legal puzzle and start treating it like a public health crisis. The math is simple: more generics = lower prices = more lives saved. Why is that so hard to get?

Alicia Hasö

January 14, 2026 AT 01:39Imagine if every time you tried to buy a loaf of bread, the bakery sued you for stealing their recipe-even though you just wanted to make your own. That’s what this is. And yet, we call it ‘innovation.’

Generics aren’t copying-they’re liberating. They’re the quiet heroes who show up in court, not with fireworks, but with lab reports and legal briefs. And for what? So a kid in Ohio can afford their asthma inhaler?

We should be giving them medals, not lawsuits.

Elisha Muwanga

January 14, 2026 AT 03:58Let’s be clear: this entire system is a betrayal of American values. We built this country on hard work, not legal loopholes. These generic companies are exploiting a law meant to protect innovation to undermine it. And now we’re supposed to cheer them on? No. This isn’t progress-it’s legalized theft dressed up as consumerism.

The brand companies invested billions. They took risks. They developed breakthroughs. And now we reward the copycats with 180 days of monopoly profits? That’s not capitalism-it’s socialism for lawyers.

If you want cheap drugs, stop enabling the cheaters. Strengthen patents, not weaken them. America doesn’t win by copying-it wins by leading.