Relative vs. Absolute Risk Calculator

Your Actual Benefit

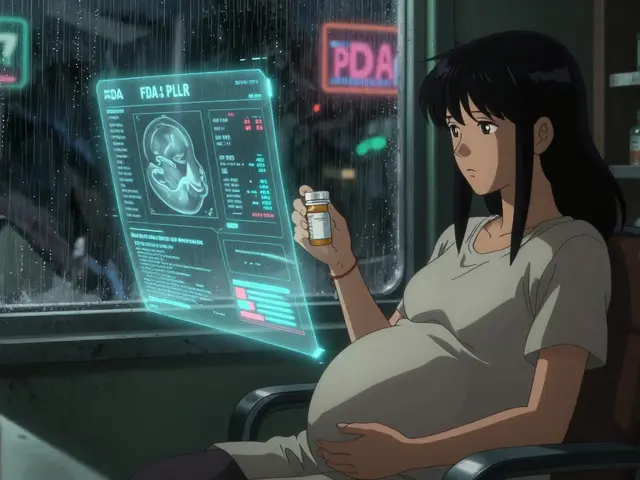

When you pick up a new prescription, the tiny print on the drug label isn’t just legal fine print-it’s your roadmap to understanding whether the medicine will help you more than it might hurt you. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires every drug to include a risk-benefit statement, but most patients don’t know how to read it. And that’s a problem.

What Does the FDA Actually Say About Benefits and Risks?

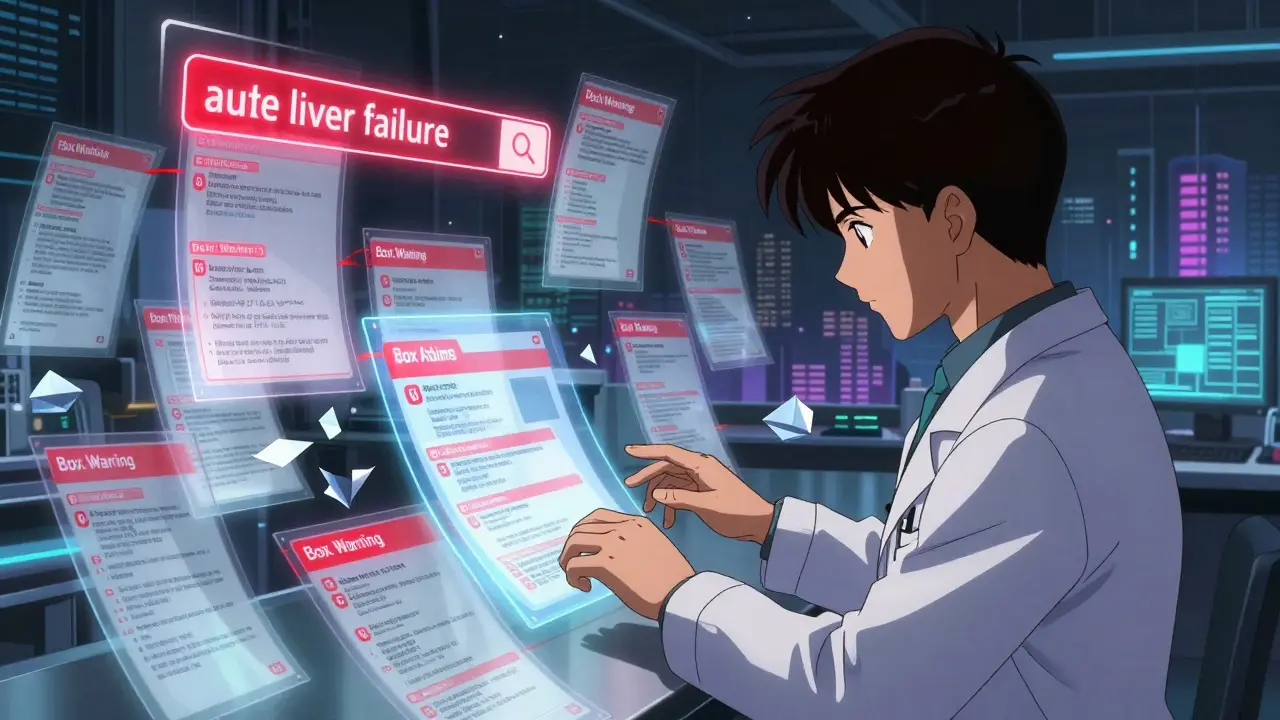

The FDA doesn’t just approve drugs because they work. They approve them only if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks for the people who will use them. That’s the core of their Benefit-Risk Framework, updated in December 2021. It’s not a guess. It’s a structured review done by teams of doctors, statisticians, and pharmacologists who look at every piece of clinical trial data, every reported side effect, and every long-term outcome. For example, if a new cancer drug extends life by an average of 4 months but causes severe nausea in 60% of patients, the FDA weighs that trade-off. They ask: Is that extra time meaningful? Are there other options? Can the side effects be managed? The answer goes into the drug’s label under Sections 5, 6, 8, and 14-parts most patients never read.Why Most Patients Can’t Make Sense of the Label

You might see something like: “Increased risk of serious heart rhythm problems.” Sounds scary. But what does that mean for you? Is it 1 in 100? 1 in 1,000? 1 in 10,000? The label rarely says. A 2022 survey by the National Health Council found only 22% of patients felt confident interpreting risk-benefit info in drug labels. For those with lower health literacy, that number dropped to 9%. Why? Because labels are written for regulators, not people. Take a common stat: “Reduced risk of heart attack by 25%.” Sounds great. But if your baseline risk is 4% over 5 years, a 25% reduction means going from 4% to 3%. That’s a 1% absolute benefit. That’s not nothing-but it’s not a miracle either. Most labels don’t explain the difference between relative and absolute risk. And that’s misleading.What Makes a Good Risk-Benefit Statement?

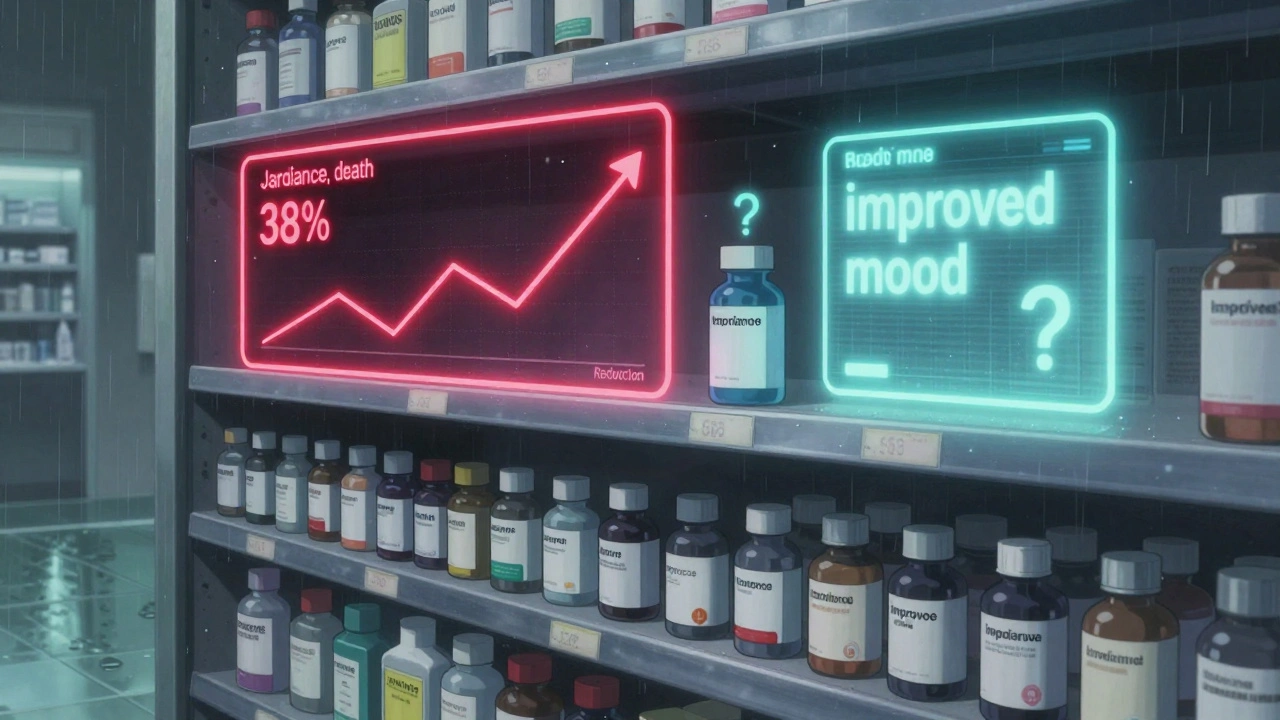

Some labels are starting to get better. Jardiance, a diabetes drug, is one of the few that does it right. Its label says: “In adults with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, JARDIANCE reduced the risk of cardiovascular death by 38% (10.5% with placebo vs. 6.5% with JARDIANCE).” That’s clear. It gives you numbers. It tells you who it’s for. It compares the drug to no treatment. That’s what patients need. The FDA now encourages this kind of language. Their 2023 pilot program requires six new oncology drugs to include a “Patient Benefit-Risk Summary” written at a 6th-grade reading level. These summaries use simple words, short sentences, and visual icons to show benefit versus risk. Imagine a bar chart showing: 7 out of 10 people saw improved symptoms. 1 out of 10 had a serious side effect. That’s easier to understand than a paragraph full of medical jargon.

How the FDA Compares to Other Countries

The U.S. approach is flexible but inconsistent. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) uses a more math-heavy method called PrOACT-URL, which assigns numbers to benefits and risks. The UK’s MHRA even asks patients directly: “How much risk are you willing to take for a 10% chance of improvement?” The FDA doesn’t do that yet. But they’re trying. In 2023, they partnered with the National Institutes of Health to test simple icons-like a thumbs-up for benefit, a warning sign for risk-that show the relative size of each. These are being tested in 12 clinics with 1,500 patients. The goal? To make risk-benefit info feel less like a legal document and more like a conversation between you and your doctor.What’s Holding Back Better Labels?

It’s not just about writing better words. It’s about time, training, and culture. FDA reviewers spend 40 to 60 hours per drug just writing the benefit-risk summary. That’s a lot. And not every drug gets the same level of detail. Cancer drugs often have clear survival numbers. Psychiatric drugs? Not so much. Benefits like “improved mood” or “reduced anxiety” are harder to measure. Risks like weight gain or sexual dysfunction are common but rarely quantified. Also, drug companies aren’t always eager to highlight risks. They want to sell the drug. That’s why the FDA now requires sponsors to submit “patient preference studies” for breakthrough therapies-essentially asking real patients what they value most. Only 17% of new drugs approved in 2022 had any kind of visual benefit-risk summary. But that’s changing. By 2026, experts predict nearly half of new labels will include them.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to wait for the FDA to fix everything. Here’s how to make sense of your own drug label:- Look for numbers. If it says “reduced risk by X%,” ask: “Reduced from what to what?”

- Check the population. Is the study done on people like you? Age? Health conditions? Other meds?

- Compare to alternatives. Does the label mention other treatments? If not, ask your doctor.

- Ask your pharmacist. They’re trained to translate label language into plain terms.

- Use the FDA’s website. Search for your drug at accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/-you’ll find the full prescribing info, including the official benefit-risk summary.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

This isn’t just about reading labels. It’s about trust. When patients don’t understand the risks, they either avoid helpful medicines or take ones that might hurt them. Both outcomes are dangerous. The FDA knows this. That’s why they’ve spent years pushing for patient-centered communication. The 21st Century Cures Act and FDA Reauthorization Act forced them to listen to patients-through surveys, focus groups, and public comments. Over 1,200 patients told the FDA: “Tell us what this means for me.” Now, slowly, they’re listening.What’s Next for FDA Labels?

By 2025, the FDA plans to require standardized benefit-risk metrics for major drug categories-like heart disease, diabetes, and depression. That means consistent ways to measure and present benefit and risk across all drugs in the same class. They also plan to make patient-facing summaries mandatory for all breakthrough therapies. That’s a big step. It means if you’re getting a new, fast-tracked drug, you’ll get a plain-language summary right on the label. And eventually? The goal is for every patient to open a drug box, read the label, and say: “I get it. This is worth it-for me.”What’s the difference between relative risk and absolute risk in FDA labels?

Relative risk sounds bigger-it says something like “reduced risk by 50%.” But absolute risk tells you the real change: “went from 4% chance to 2% chance.” A 50% drop sounds impressive, but if your original risk was tiny, the actual benefit is small. Always look for both numbers.

Why don’t drug labels always say how common side effects are?

They should, but often don’t. Some labels list side effects without frequencies, like “may cause headache.” That’s vague. The FDA now requires “common” (≥1/10), “uncommon” (≥1/100 to <1/10), and “rare” (≥1/10,000 to <1/1,000) categories-but not all companies follow this perfectly. If it’s not clear, ask your doctor or check the full prescribing information online.

Can I trust the FDA’s risk-benefit assessment?

Yes, but understand it’s based on population data, not your personal situation. The FDA looks at what works for most people. You might be different-your age, other conditions, or how your body reacts. That’s why your doctor’s input matters. The label is a starting point, not the final word.

Are newer drugs safer than older ones?

Not necessarily. New drugs are tested on smaller, healthier groups for shorter times. Long-term risks often show up only after thousands of people use them for years. Older drugs have more real-world data. A drug approved in 2020 might have fewer side effects reported-but that doesn’t mean it’s safer. It just means we haven’t seen all the risks yet.

Where can I find the official FDA risk-benefit summary for my drug?

Go to accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/, search your drug name, and click “Full Prescribing Information.” Scroll to Section 14 (Clinical Studies) and Section 6 (Adverse Reactions). The benefit-risk conclusion is usually in the first few pages of the Highlights section.

If you’re unsure about your medication, don’t guess. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist. Bring the label. Ask: “What does this mean for me?” That’s the best way to turn confusing text into clear decisions.

Clare Fox

December 6, 2025 AT 15:01so like... if my blood pressure med cuts my risk of stroke from 4% to 3%... that's still a 25% relative drop? but i'm basically just moving from 'maybe' to 'probably not'? why does pharma talk like this is a miracle?

Billy Schimmel

December 7, 2025 AT 00:57lol at how the FDA makes cancer drugs sound like life-saving miracles but for depression? 'may cause weight gain and low libido' and that's it. no numbers. no context. just vibes.

Akash Takyar

December 8, 2025 AT 15:25It is imperative to note that the FDA’s framework, while imperfect, represents a significant advancement in patient-centered pharmacovigilance. The inclusion of patient preference studies for breakthrough therapies is not merely procedural-it is ethical. We must encourage, not deride, this incremental progress.

olive ashley

December 10, 2025 AT 07:38they’re lying. the whole system is rigged. if you read the whistleblower reports, 70% of the 'clinical data' is cooked. the FDA takes bribes from big pharma. your 'benefit-risk' is just a marketing brochure with a footnote.

Priya Ranjan

December 10, 2025 AT 22:40You people don’t even know how to read a label? This is why America is falling apart. If you can’t understand basic statistics, maybe you shouldn’t be taking pills at all. Stop blaming the FDA. Take responsibility.

Gwyneth Agnes

December 12, 2025 AT 20:48just tell me if it’ll kill me or help me. that’s it.

Shayne Smith

December 12, 2025 AT 22:11my pharmacist just handed me a sticky note with 'take this, don't panic, call if you turn purple' and that was more helpful than the whole 12-page label.

Katie O'Connell

December 14, 2025 AT 08:53The superficiality of the FDA’s current approach is lamentable. While the adoption of visual icons is aesthetically pleasing, it risks infantilizing patient autonomy. True empowerment lies in granular, statistically rigorous disclosure-not emotive pictograms.

Inna Borovik

December 16, 2025 AT 02:39Let’s be real: the only thing worse than a drug label is the fact that the same company that made the drug also wrote the patient summary. That’s like letting the fox design the chicken coop.

Karen Mitchell

December 17, 2025 AT 17:31Why are we even talking about this? The FDA doesn’t care about patients. They care about lawsuits. If you die from a side effect, it’s 'unforeseen.' If you live, it’s 'a triumph of science.'

Chris Park

December 17, 2025 AT 19:03Did you know the FDA’s 2023 pilot program was secretly funded by Pfizer? The 'icons' were designed by a marketing firm. This isn’t transparency-it’s rebranding.

Kay Jolie

December 18, 2025 AT 10:14As a pharmacoeconomist with dual degrees in biostatistics and narrative medicine, I must emphasize that the current paradigm of benefit-risk communication is fundamentally incommensurable with the phenomenological experience of chronic illness. The FDA’s reliance on quantifiable metrics ignores the ontological weight of lived suffering.

Max Manoles

December 20, 2025 AT 07:09I’ve been reading these labels for 15 years as a clinical researcher. The Jardiance example? That’s the gold standard. Clear numbers. Clear population. No fluff. Why can’t every drug do this? Because it takes time. And time costs money. And the system doesn’t reward honesty-it rewards speed. The FDA’s trying. But they’re drowning in paperwork and corporate pressure. We need to fund them better, not mock them. The fact that they’re even testing icons? That’s progress. We just need to push harder.